Kenneth Kaunda the treacherous Communist

In power, ruling under a State of Emergency Law from 1964 to 1991

The Communist Pig that wanted to be emperor of ZambiaCRIME

It is important to note that Zambia is a key transhipment point for the global illegal drug trade. A significant quantity of heroin and cocaine bound for Europe and for distribution throughout the rest of Southern Africa passes through Zambia. This illicit trade is supported by the fact that Zambia is a regional money-laundering centre that acts as an excellent facility for those dealing in drugs to disguise the illegal source of their profits.

LIST OF CRIMES AGAINST THE BAROTSELAND

- The Looting of the Barotse Treasury.

- The wanton murders of Barotse activists.

- The unilateral abrogation of The Barotseland Agreement 1964.

- The victimisation of several Barotse Nationals employed in Zambia.

- The subtle form of economic blockade imposed on Barotseland for years.THE FIRST REPUBLIC

The First Republic (1964-1972) was formed at independence in 1964. In multiparty elections in 1964 the United National Independence Party (UNIP) defeated its main rival, the African National Congress (ANC). The socialist-"humanist" orientation of the government (led by President Kenneth Kaunda) was bolstered by a large revenue supplied by high international copper prices, which allowed the opening of health and education services to the black population. The UNIP could boast a considerable success; by 1972 Zambia's hospitals had grown by 50 percent and health clinics doubled, whilst the availability of education services also dramatically increased. In order to administer the growing public sector the civil service expanded dramatically and acted as a mechanism for the UNIP ruling elite to award the party faithful. Due to the lack of a significant business sector, civil servants became the nation's upper class.

THE SECOND REPUBLIC

The Second Republic (1972-1990) was established in 1972. Known as the "one party-participatory democracy," it was a one-party state ruled by the UNIP. All other political parties were banned, and Kaunda's dominant role in the UNIP and the government assured him an uncontested rule. However, the Second Republic ran into serious difficulties due to corruption within the civil service, government, and parastatal sector, and declining government revenue caused by the falling price of copper. The government began to borrow heavily to support the vast state expenditure and the country became highly indebted.

Discontent grew throughout the country over the 1980s because of rapidly declining incomes and rising prices, partly caused by an IMF economic liberalization program (which was subsequently dropped in 1987). The culmination of worker militancy, student protests, and growing opposition within the ruling class was the formation of the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) led by Frederick Chiluba (a key trade union figure). Mounting economic crisis and political pressure led Kaunda to sign a new constitution in 1990, putting an end to one-party rule.Kaunda and UNIP militia be tried at The Hague for Crimes against Humanity?

By Malama Katulwende

Many of the women and children had stakes thrust into anus or vagina or down their throats – this is how they were tortured to death

The massacre of the Lumpa adherents by the United National Independence Party (UNIP) militia and the Zambian security forces is perhaps the darkest chapter in the story of the regime of Kaunda. An army officer – who witnessed the atrocious killing of Lumpas at Paishuko settlement in eastern Zambia, on August 7th 1964 – narrated the shocking experience as follows:

“Many of the women and children had stakes thrust into anus or vagina or down their throats – this is how they were tortured to death.”

This description is captured in John Hudson’s book, “A Time To Mourn” in which some official police photographs of the monstrous event depict a man with a stake hammered into his mouth, burnt corpses, and a woman who, after being repeatedly raped, had the skin of the inside of her thighs torn off.

Between July and September 1964 when the Lumpa-UNIP war started, over twenty thousand Lumpa faithful fled the country and settled in the Katanga province of the Congo. It is also estimated that at least two thousand members of the sect were killed by government soldiers alone, though official sources claim the figure to be slightly lower. The statistics, however, exclude thousands more who were wounded, and others who died from starvation, sickness and trauma on their journey into the Diaspora.

Significant though the Lumpa conflict is to our appreciation of Zambian historiography, the Zambian government has, however, imposed a curtain of silence over this dreadful event. The Lumpa sect and ideology are not taught in schools, nor are objective narratives of the war and Diaspora of Lumpa officially admitted as part of our social memories. The burnt churches and mass graves of the Lumpa are not recognized nor celebrated as memory sites. The whole episode of murder and destruction has bee banished from the public domain as though nothing had happened.

This article, however, briefly looks back at the events which eventually led to the apocalypse – the Lumpa Church war with the UNIP militia and colonial government of Northern Rhodesia.Kenneth Kaunda and UNIP activists should be tried at The Hague for their involvement in the massacre of members of the Lumpa Church.

The demise of the Lumpa Church in Zambia and the genocide and dispersal of its members in the early 1960s has been a focus of several studies. Andrew Roberts’ article, “The Lumpa Church of Alice Lenshina,” W.T. van Binsbergen, “Religious Change in Zambia: Exploratory Studies”, Hugo Hinfelaar, “Women’s Revolt: The Lumpa Church of Lenshina in the 1950s”, Jean Loup Chalmette, “The Lumpa sect, rural reconstruction, and conflict”, David Gordon, “Beyond Ethnicity: narratives of war and exile of the Lumpa Church,” and more recently, Gordon, “Rebellion and Massacre? The UNIP-Lumpa Conflict Revisited,” as well as two less scholarly works, “A Time To Mourn” by John Hudson, and “Blood on Their Hands” by Mulenga, have all reconstructed the terrible conflict from various perspectives.

Out of the population of 448,300 in the north-eastern Zambia, for example, an estimated 90,000 people were registered Lumpa members with 119 churches

They have looked at the Lumpa ideology, the political and class challenge of the Lumpa Church, UNIP militancy and the nationalist struggle for independence, and the religious separatism of the Lumpas. What these studies have not done, though, is demand the trial of Kaunda and UNIP activists for crimes against humanity and compensation by the Zambian government for the role it played in the annihilation of the Lumpa Church. This omission may be excusable because these studies are purely historical.

Yet according to these accounts, Alice Lenshina Mulenga, founder and spiritual leader of the pan-Africanist Lumpa Church in Chinsali, Northern Province, defied Kenneth Kaunda’s UNIP directives to conform to demands to oust the white-settler regime from power in Northern Rhodesia.

She denounced politics and encouraged her followers to “seek ye first the Kingdom of God”. Unfortunately, this defiance against political authority, especially against a political authority which was to form the first ever Black government on October 24th 1964, and the formation of a separatist, religious sect whose beliefs and rituals were at variance with accepted, traditional values of European Churches and African cultural values such as chieftaincy, polygamy and sexual cleansing, alienated the Lumpa Church.

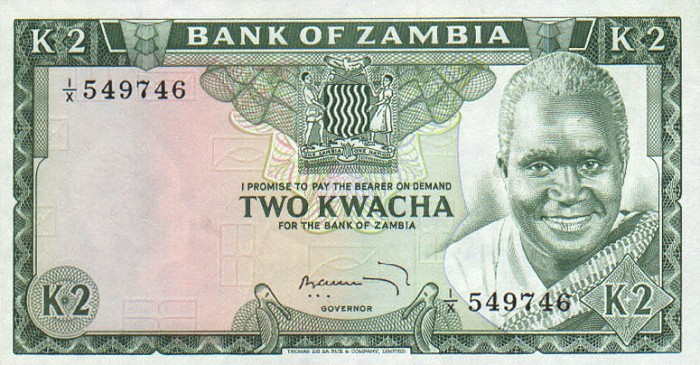

Kaunda (1964) handed over Power used to kill people

In their desire to escape from social, political and religious estrangement and violent attacks from UNIP cadres, the Lumpa Church members established settlements in Chinsali, Kasama, Mpika, Isoka and Lundazi. At its peak in 1960, the Lumpa Church had membership which outstripped that of all other churches in Northern Province and flourished in other areas such as Lusaka, Copperbelt, Kabwe, Livingstone and Zimbabwe. Although he sect had started off as a Bemba phenomenon, it later transcended cultural boundaries by drawing converts from other churches and tribes.

Out of the population of 448,300 in the north-eastern Zambia, for example, an estimated 90,000 people were registered Lumpa members with 119 churches. In 1964, however, the objects of political militants in the struggle for independence and the simple, benevolent and separatist teachings of the Lumpa Church were destined to clash.

Dr. Kenneth Kaunda, who was Prime Minister of the coalition government of UNIP and ANC, ordered the annilation of the stockaded, Lumpa settlements when the Lumpas refused to heed the deadline to relocate back to their former villages. Using automatic weapons the Zambian soldiers attacked the Lumpa headquarters, Sione, on July 30th 1964. Mercy Mfula remembered the event in Gordon’s work, “Rebellion or Massacre?

The UNIP-Lumpa Conflict Revisited” like this:“We heard the sound of guns. We ran into houses to hide. Our friends were being shot. We heard others calling: ‘Come and see your friends are dead.’ We ran up and down; we saw people shout, some dying. The guns the soldiers used started from ground level and then rose to treetops. Chickens died, goats died, and trees lost their leaves. We ran up and down. Old people were crying. There was confusion. We kept saying, ‘God, what has happened?’”

The purge of the Lumpa Church members and their dispersal into the Congo by UNIP and government forces raises some questions. Was the force used proportionate to the “threat” of the Lumpa Church? Was the sect entirely to blame for the massacre? What legal basis was there to justify the slaughter of defenseless women and children, or ill-equipped Lumpas who dared the British military in defense of their faith?

There is evidence to suggest that the Lumpa Church denounced the teachings of the foreign based churches, indigenous authority and occasionally attacked UNIP activists who were intolerant of their faith. Violent, physical skirmishes, indeed, took place between the Lumpas and UNIP cadres over the former’s refusal to buy party cards or attend political meetings on Sundays. Yet to just the use of brute force against the sect in the manner it was done is preposterous.

However, Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe, a staunch ally of Kaunda advocated for the extermination of the Lumpa Church:

“Lenshina, and her adherents…People who eat their dung, washed their bodies with their own urine […] change into a devil, even five times worse than a devil, they actually would be wild beasts. When you find a wild beast eating in your gardens or trying to kill: what d you do? You would come together and start to follow it till it is dead. And even after death, you would break its legs, spit on it and roast it above the fire till nothing is left anymore. Our government is determined to destroy this wild beast.”

These sentiments were irrational. They demonstrated a pathological hatred against the sect which cut across all UNIP cadres. Ironically, though, Kapwepwe himself would be a victim of Kaunda’s dictatorship and intolerance and would be associated with Lenshina, who was captured and jailed without trial until her death in 1978.

But Kaunda, whose own mother, Hellen, was a Lumpa member, and his own brother, Robert, composed songs for the sect, was to say of Alice Lenshina and the destruction of the church:

“I have no intention whatsoever of again unleashing such evil forces. Let me end by reiterating that my government has no desire whatsoever to interfere with any individual’s religious beliefs but such a noble principle can only be respected where those charged with the spiritual, and I believe moral side of life, are sufficiently responsible to realize that freedom of worship becomes a menace and not a value when their sect commits murder and arson in the name of religion.”

Indeed, Kaunda might have been right to suggest that some members of the Lumpa sect did, in fact, commit murder and arson in retaliation against UNIPISTS who torched their churches, food stores and assaulted their members. Yet it is certainly false to claim that all Lumpa members, wherever they were, committed murder and arson in the name of their sect. To cite an example, the District Commissioner at Isoka, John Hudson, who took part in the destruction of the Lumpa settlement at Chanama, said:“I felt deeply sorry to have to uproot [the Lumpas] and destroy their well, built-settlement, which represented months of work. Destruction of the church was particularly distasteful. These people had never been aggressive towards their neighbors; it was simply their misfortune that they belonged to a church which had chosen a course of violence elsewhere…”

Of course, as a government official, Hudson was bound to defend the government by blaming the Lumpa Church. However, there is evidence to suggest that the Lumpa retaliation and violence against those who were against them was in response to the failure by the authorities to curtail UNIP-instigated attacks. Several times Lenshina begged the government to protect her members. When this failed, the sect left their traditional villages and established their own settlements away from the UNIP violence.

On the other hand – assuming that Kaunda sought to preserve law and order – then why were activists who destroyed Lumpa churches and murdered its members rarely arrested but hailed as ‘freedom fighters’? At Paishuko in Eastern Province, for example, an entire settlement of Lumpa members who comprised women and children were tortured and exterminated by UNIP loyalists with the 1NRR soldiers nearby. Why did the government troops choose not to protect the settlement from UNIPISTS?It is also surprising to observe that despite the fact that the members of the Lumpa Church were only armed with primitive spears, axes and bows and arrows, Kaunda decided to use the 7.62mm NATO self-loading automatic rifles.

The government also sent over two thousand well, trained troops who fired shots even where there was no resistance from the Lumpas. Kaunda did not use the police who were specifically trained to deal with cases of law and order. This explains, though, the disparities in casualties. Less than ten government soldiers were killed or wounded by the sect, whereas the government massacred over two thousand Lumpas who included women and children. The victims were hastily buried in mass graves without any ceremony. The documents which implicated civil servants in the massacre have since vanished. But why were the documents destroyed if government sanctioned killing of the Lumpas was correct? What was the government afraid of if they were right? Why has there not been any official state discourse in the writing of textbooks for use by children in high schools, or even tertiary institutions?

The annilation of the Lumpa Church has, however, had serious consequences. Not only were over twenty thousand sect-members forced into exile in the Congo, there were at least two thousand people killed by the government troops which should have protected them. Thousands more victims were wounded, or lost their lives from starvation, trauma as they took flight. This destruction of lives, property and displacement of Zambians by Kaunda and the UNIP is not only morally repugnant but criminal as well.

It is more than forty-six years since the tragedy happened. The majority of the Lumpas still live in exile in the Congo, while those who decided to either remain or return set up churches in different parts of the country. Their banishment under the Preservation of Public Security Act has not prevented them from keeping their faith. But strange to narrate, until the late 1990s their church had continued to suffer humiliation, torture, banishment and death, even when they were no longer living in their home country. For fear of a Lumpa attack from Mukambo, for example, the government of Zambia persuaded the Congolese government to force the Lumpa communities into the interior, or surrender them to the Zambian authorities. Unfortunately for the government, the Lumpa Church is still alive today.

In summing up, therefore, we have sketched the social, political and ideological context in which the Lumpa Church of Alice Lenshina, on the other hand, battled the government and UNIP activists prior to independence. We have suggested that although Lumpa adherents occasionally attacked UNIPISTS, the full responsibility for the Lumpa-UNIP war should be born by Kaunda’s government and the UNIP militants, who unleashed a highly trained army to crash Lumpa factions armed with axes, spears, bows and arrows. We have also said that the force used against the Lumpas was not proportionate to their ‘threat.’

FFSAFederation of the Free States of Africa

Contact

Secretary General

Mangovo NgoyoEmail: [email protected]

www.africafederation.net

Kenneth David Kaunda , President of Zambia, Kenneth David Kaunda , President of Zambia, Kenneth David Kaunda , President of Zambia, Kenneth David Kaunda , President of Zambia, Kenneth David Kaunda , President of Zambia, Kenneth David Kaunda , President of Zambia, Kenneth David Kaunda , President of Zambia, Kenneth David Kaunda , President of Zambia,